And suddenly, it’s the end of 2024. Last time, I thought about 2024 in terms of song, this time I’m looking at it in terms of games.

Freeform Games

Freeform Games had a good year. In some ways it was not quite as good as 2023, but in other ways, better. I’ll write more about it on the Freeform Games blog, when the final numbers are in (so sometime in January).

Conventions and games weekends

I love going to conventions – I think my gaming high points have all been conventions. I enjoy them as much for meeting old friends as playing the games – and doing both is best.

In 2024 I attended:

West End Lullaby (February, Retford): The annual weekend-long freeform is back in its usual home, Retford. I played Aaron Burr and had a whale of a time in this crazy freeform based on West End musicals.

Airecon (March, Harrogate): A lovely local convention in Harrogate. I ran three tabletop RPGs and played lots of board games. As far as board games go, it’s my favourite convention.

LarpCon (March, Coalville): A convention all about larp. Mostly full of people selling stuff. It was okay, but reminded me that the freeform community is terrible at selling ourselves. I am not sure I want to go again.

Peaky (April, not far from Tamworth): I’ve been to every Peaky since it started in the early 2000s. It’s my favourite gaming weekend of the year: intense, creative and fabulous. I wrote one game and played two.

UK Games Expo (June, NEC Birmingham): UKGE is at the back end of the summer half term holiday, and because we’re normally away that week, I rarely go. This time I knew I was free, so I drove down for a day. UKGE is tiring, busy and crowded. It was okay, but I don’t feel the need to go back anytime soon.

Continuum (July, Leicester): Continuum was exciting for me for two reasons. First, Continuum moved to the Cranfield Management Centre – perhaps the best space for a convention that I’ve been to. Second, I took Megan with me. Luckily, she had a great time and wants to go to Continuum next year.

Furnace (October, Sheffield): Always a delight, Furnace is tabletop roleplaying only, and local enough that I don’t need to stay overnight. I ran one game and played in three.

Consequences (November, Chichester): Longest time away (four nights), I ran two freeforms and played in five and ran a game of Hillfolk. Too much gaming? Maybe.

Plans for 2025: Mostly the same, although I won’t go to UKGE, and I’m unlikely to go to LarpCon.

I also feel there ought to be something in Leeds. I wonder who I have to talk to about starting something up?

Freeforms

I played in or ran sixteen freeforms in 2024, which feels like a good year but is nowhere near the record of 20 in 2023. This year I ran six freeforms and played ten.

|

| Best photo of me this year - taken for Home of the Bold at Continuum |

In terms of writing, I finished and ran The Stars our Destination twice, once online and once at Consequences. I also got Backstage Business published for Freeform Games (and ran it at Continuum). I have also put together a short freeform, The Show Must Go On!, for Freeform Games that I have just sent out for playtesting. And I published All Flesh is Grass and Children of the Stars.

Favourite to run: The Stars our Destination at Consequences, which went really smoothly. I also ran Murder on the Istanbul Express for Megan’s 18th birthday in our garden, which went really well.

Favourite to play: Do You Hear The People Sing by Alex Helm was just so much fun that it was my favourte freeform of 2024 by a mile.

Plans for 2024:

- Write and run the game that follows The Stars our Destination – set on Callisto. (It doesn’t have a title, yet.)

- Then start work on getting Messages from Callisto ready for publication.

- Publish The Show Must Go On! via Freeform Games.

Tabletop RPGs

2023 was a little hit and miss in terms of TTRPGs. My regular group had to cancel rather often due to health issues – something I suspect will only increase as we all get older.

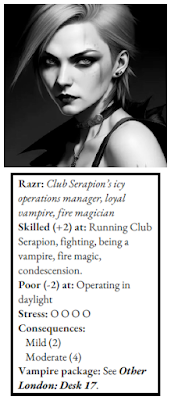

In terms of numbers, I played more Fate Accelerated than anything else in 2024. Good Society came second, with Most Trusted Advisors and DramaSystem (Hillfolk and others) tied for third place.

I playtested and published The Dead Undead, an investigation for Other London: Desk 17.

Favourite to run: I loved running The Dead Undead – it was very satisfying, although it took a lot longer than I expected.

Favourite to play: Good Society, which we started in 2023, was so much fun, and I had some of my single favourite sessions this year.

Plans for 2024:

- Playtest the two scenarios I have written for the Department of Irregular Services (for Liminal) and then publish them.

- Write an investigation for The Dee Sanction.

- Continue working on The Orphan Room for https://fourlettersatrandom.blogspot.com/2022/11/liminal-department-for-irregular.html. It would be nice to get it to a point where I’ve tested it. But I’m aware I’ve got a lot of other projects going on.

Boardgames

In 2023, I played more games of My City than any other game. (That’s the same as 2024!) This year I played a legacy campaign on Boardgamearena, which I enjoyed. (The full campaign is 24 episodes, and it took the four of us about six months to play it.)

An honourable mention goes to Ticket to Ride: Legacy of the West, a legacy game. We’ve got two more games to play, but I’m really enjoying it. (Yes, the criticisms are valid – the early games are very short and the later games are very long. But I’m still enjoying it.)

New games to my collection:

Kavango: Collect animals for your reserve in this drafting game with similarities to 7 Wonders. I backed this on Kickstarter, and have enjoyed the handful of games I’ve played with the family. It’s got a nice theme and design – but takes up quite a bit of space on the table.

The Crew: The Quest for Planet 9. A Father’s Day gift, and one I took on holiday over the summer. It’s a cooperative trick-taking game which we enjoyed, but curiously haven’t played since we came back. (Kavango took over.)

The Mind: A deceptively simple game about emptying your hand without communicating. Really good filler with the right group.

6 Nimmt: Excellent game that plays with up to 10 players (!) – simultaneously. I’ve played this with friends but not with the family yet.

D-Day Dice expansions: D-Day Dice was the first game I ever Kickstarted, and I backed the second edition as well. D-Day Dice is a dice-rolling push-your-luck game of storming the beaches on D-Day. It plays really well solo, and I enjoy it a lot. This year, several expansions turned up for it – I now have enough D-Day Dice goodness to last me for years. (But there’s more planned…)

Plans for 2024: Play more games! Always! No doubt my games collection will swell – at least until I get rid of some of it. Already on order is Innovation Deluxe (card-based craziness from Carl Chudyk), due early next year. And D-Day Dice: Pacific Kickstarts in January. I expect I’ll back that.

Video games

And I played more World of Tanks Blitz than is probably healthy. It’s probably time I uninstalled it again.

And overall?

2024 was great for games. I feel very lucky I’m able to play so many games.

/pic7976828.jpg)

/pic5266901.jpg)