It’s not often that I read a roleplaying game and can’t wait to get it to the table. Microscope was one (a story game rather than a “proper” RPG, but even so) and Hillfolk another (although that took me years to play). Most Trusted Advisors, a Forged in the Dark game by W.S. Healed & Citizen Abel is another.

Most Trusted Advisors

is a 54-page “comic game of feudal intrigue.” The players take the roles of a profoundly incompetent monarch’s eponymous privy council. As lords and ladies of the realm, they must keep their liege safe from foreign agents, court conspiracies, and their most dangerous enemy: their own incompetence. The GM gets to play the monarch – The Liege.So it’s the game of Blackadder II. The GM plays Queenie, while the players are Blackadder, Lord Melchett, Malcolm Tucker, Moist von Lipwig and others.

What’s not to love?

Setting

Most Trusted Advisors is set in the fictional city of Valdrada, the capital of the feudal realm of Dulcinea.

Valdrada is a mashup of 15th-century Florence, 13th-century London, and 11th-century Paris. It’s a city of castles, slums, sprawling streets, busy markets, theatres, taverns and brothels.

A few truths about Dulcinea:

- It’s ruled by a Liege, a blithering royal shit with immense political power. Their Most Trusted Advisors are the ones actually running the realm.

- The Nobility occupy most positions of political, social, and economic power. They are all to the last man either useless or malevolent, often both.

- The Burghers, city-dwelling merchants, occupy the rest. They’re equally useless and malevolent, but usually better at hiding it.

- The Church is a powerful institution that demands belief in their god or gods. Some people believe in witches and sorcery, which may or may not be real.

- It’s neighboured by the Duchy of Zobia, a bitter historical enemy. A Great War has been fought, and the ink is still drying on the treaty.

- Thousands of peasants slave away thanklessly to keep the realm running.

Plus, the players get to add their own truths as part of the game setup.

This melting pot background means never having to worry about being historically accurate – or accidentally offending someone. (And Most Trusted Advisors definitely doesn’t want to offend.)

Would Most Trusted Advisors work if it were set in Elizabethan England? I’m sure it would, but I’m not a history buff and I’m happy to set it in a nonsensical world and not worry about accuracy.

Rules

Most Trusted Advisors uses a stripped-down Forged in the Dark engine. At least, I assume it’s stripped down because there’s really only one roll: Action rolls.

Anytime a character is attempting something dangerous (or uncertain), they make an Action roll. To do this, they pick an appropriate action rating (such as Bluster to lie or bluff) and then roll a number of d6s equal to their rating. Ratings range from 0 to 4, and you pick the highest result. A six is a success, a 4-5 is a partial success and a 1-3 is a tragedy.

Tragedies and partial successes attract misfortunes, which are conditions such as Angry or Enemy of the Crown.

That’s pretty much it for the rules. There are some fiddly bits such as flourishes (sort of enhanced actions), twists (spend them to avoid misfortunes and do other things), Ducats (bennies), and arms (countdown clocks shaped like shields).

There are also fortune rolls, which are used to answer questions like “How good is the feast’s dessert?” You build these like action rolls, but really, they’re the kind of thing I would roll 2d6 for and interpret the result, high = good, low = bad. That kind of decision-making is part of my GM tookit – it feels weird to have a game specifically tell me how to make those rolls. (Yes, I realise fortune rolls are from Blades in the Dark.)

Playbooks

The six playbooks in Most Trusted Advisors are delightful.

- The Treasurer, a persnickety, long-suffering bean counter

- The Lover, a charming, naïve consort to the monarch

- The Alchemist, a brilliant but unhinged occultist

- The Hierophant, a pompous, self-righteous priest

- The Marshal, a bold, hot-headed general

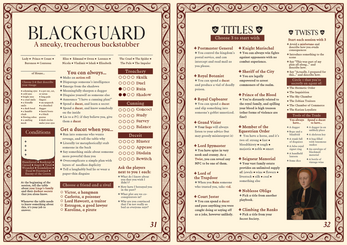

- The Blackguard, a sneaky, treacherous backstabber

Abilities are described as “titles”, which is nicely thematic. You choose three as part of character generation, and they’re things like:

- Keeper of the Swans: As a Twist, you can unleash angry, escaped swans wherever you please

- Royal Librarian: You can spend a ducat and know of a book that can tell you exactly what you need to know.

- Lord Spymaster: You have spies in every nook and cranny. As a Twist, you can reveal any NPC to be one of them

(The one I don’t like is “Noblesse Oblige: Pick a title from another playbook.” Not because I don’t like picking another title, but because it’s messy and it requires either more mastery of the game than is likely amongst my players, or too much dreary analysis paralysis. [I don’t like this option in PbtA games, either.])

So the characters are great. Don’t tell me you don’t want to play right now.

Secret societies

And of course there are secret societies! Six of them, each with agendas, contacts and even more titles. The agendas give players extra objectives – more things to do.

- The Hermetic Order: Secretive occultists in search of metaphysical truths

- The Inquisition: Religious fanatics looking to punish sins, real or imagined

- The Sky Chamber: There is no such organization as the Sky Chamber

- Zobian Traitors: Seditious and cunning spies, loyal to the Duke of Zobia

- The Chamber of Commerce: Wealthy burghers and merchants conspiring for profit

- Karian Loyalists: Staunch traditionalists still loyal to a long-deposed dynasty

The Liege

The GM, meanwhile, plays the Liege, an unpredictable, irresponsible idiot. So Queenie or the Prince Regent from Blackadder. Lieges come in different flavours, each with their own playbooks:

- The Royal Buffoon is the median wealthy jackass.

- The Have-at-Them is an upstart warmonger.

- The Bleeding Heart is terminally afflicted with noblesse oblige.

- The Loathsome Toad mistakenly thinks they’re a master of intrigue.

- The Powder Keg is a paranoid tyrant always looking for someone to behead.

Liege playbooks come with a list of characteristics and two signature Misfortunes and Mishaps. (Misfortunes happen when the dice are rolled, as mentioned above. Mishaps are things the GM can do to kick a session off, or during a lull in the game – along the lines of GM moves in other games.)

I suspect I’ll pick the Royal Buffoon for my first game, but they all sound like fun.

But what do you do?

Once characters have been created, the Liege starts everything off with a mishap. If you can’t think of anything, there’s a table of inciting incidents at the end, such as: “Your liege’s brother has claimed the throne.” As liege, you demand that your advisers sort it out – and you’re off and running.

As a player, you want to become the Liege’s most trusted advisor – the first amongst equals, as it were. Except they were never your equals.

The game ends with a footnote – where your character ends up in history. To determine your fate, you roll one dice for each of these that are true:

- You survived until the end of the game.

- You’re your Liege’s most trusted advisor (the Liege player decides who this is!)

- You completed one of your secret society’s agendas.

- You completed two or more of your secret society’s agendas.

Success lets you choose questions to answer from the legacies list (How did you permanently change the realm’s political system?); failure means choosing from the list of infamies (Why did nobody go to your funeral? What was the least convincing excuse?)

It’s worth letting the players know how the game will end so they can work towards those. Once they realise they will get dice for not dying, being the Liege’s favourite and completing their agendas, they should drive all the action.

Epilogue: There’s then a slightly odd, optional epilogue, a short mini-game called How’s it going, Geoffrey? Where you look at events from the point of view of the unluckiest peasant in the realm. It sits slightly oddly, and I’m not sure how I feel about it. I’m sure I’ll try it when I run Most Trusted Advisors, but from reading it, I’m not entirely convinced.

But it’s not perfect

Some things are explained in a bit too much detail, as if I’ve not played a roleplaying game before. Is that likely? Is anyone likely to stumble across Most Trusted Advisors without knowing what they’re getting? I suspect not, but anyway.

Fortune rolls: I’ve already mentioned fortune rolls. Making snap decisions is something every GM has to learn – yet most games don’t cover it. Does that mean it’s missing, or is it not needed?

Countdown clocks: Most Trusted Advisors takes a page to explain “Arms” – which took me a moment or two to realise it was just a new name for countdown/progress clocks. Part of me likes the way the mechanic is renamed to suit the setting, but a bigger part of me is irritated that so much explanation was needed for something that is pretty simple (and described in many other games).

Safety and inclusion: I’ve seen so many sections on safety tools that my eyes usually glaze over them. Does every game need a section on safety tools? Can we not just point to the many excellent online web pages? Apparently not.

Anyway, Most Trusted Advisors has sections on safety tools, warns not to be antisemitic when using secret societies, includes a page on queer identity and oppression, and talks about ethnicity. Even the epilogue minigame, How’s it going, Geoffrey? is there to help reflect on how awful most people’s lives were in the Middle Ages.

I know I’m a white, middle-class, middle-aged bloke, but to me, it all feels a bit heavy-handed. But maybe that’s the point – and my slight irritation reflects more on me than it does the game.

GM improvisation: Most Trusted Advisors relies on the GM to keep things going. While character creation should result in conflict and agendas, if the players don’t fully embrace the idea that they are driving the action, the game could struggle to get going.

Why I like it: ticking boxes

Most Trusted Advisors ticks many of my boxes. The key things I like in a game are:

A plot. For me, this is probably Most Trusted Advisors’ weakest area. While there’s no specific scenario, between the initial premise, character generation and the rules for determining your character’s fate, some sort of plot should present itself. However, it’s very reliant on the players – if they falter, everything then relies on the GM.

The characters are important. I like the characters to be important to whatever the game is about (my pet gripe are convention games that just use the published pregens without tying them to the adventure). Characters with a stake in what’s going on help keep their players engaged.

Players talk to each other as characters (not just to the GM). Most Trusted Advisors is slightly player-v-player, so the players should talk to each other rather than just to me. And as part of character generation, the players create shared backstories by asking each other questions.

Other points in Most Trusted Advisors favour include:

- It looks easy to run – most of my friends are familiar with Blackadder and the playbooks are full of flavour.

- It’s ideal for one-shots, and I like one-shots. (I suspect it’s exhausting to run and play, so it might even be rubbish for longer games.)

- Character generation includes choosing a friend and a rival. Why don’t more games do this?

- For the most part, it’s really nicely written.

Overall

So that’s Most Trusted Advisors. I’m looking forward to playing it – hopefully soon.

You can get Most Trusted Advisors from the creators’ page on Itch.io, here.

And click here for my report of play.

No comments:

Post a Comment